- Home

- Cindy Lynn Speer

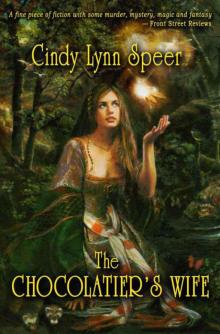

The Chocolatier's Wife

The Chocolatier's Wife Read online

Cindy Lynn Speer

THE CHOCOLATIER’S WIFE

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Copyright © 2010, 2012 by Cindy Lynn Speer

Cover art by Howard David Johnson

Design by Olga Karengina

Published by Dragonwell Publishing

www.dragonwellpublishing.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any printed or electronic form without permission in writing from the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

Kindle Edition, License Notes:

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Chapter 1

Time was, in the kingdom of Berengeny, that no one picked their spouses. No one courted—not officially, at any rate—and no one married in a moment’s foolish passion. It was the charge of the town Wise Woman, who would fill her spell bowl with clear, pure water; a little salt; and the essence of roses, and rosemary, and sage. Next, she would prick the finger of the newborn child and let his or her blood drip into the potion. If a face showed in the waters, then it was known that the best possible mate (they never said true love, for that was the stuff of foolish fancy) had been born, and the Wise Woman could then tell where the future spouse lived, and arrangements were made.

For the parents of William of the House of Almsley, this process would turn out to be less than pleasant.

The first year that the baby William’s finger was pricked and nothing showed, the Wise Woman said, “Fear not, a wife is often younger than the husband.”

The second, third, and even fifth year she said much the same.

But you see, since the spell was meant to choose the best match—not the true love—of the heart the blood in the bowl belonged to, this did not mean, as years passed, that the boy was special. It meant that he would be impossible to live with.

On his seventh birthday, it seemed everyone had quite forgotten all about visiting the Wise Woman until William, who knew this of long habit to be a major part of his day—along with cake, a new toy, and a new set of clothes—tugged on his mother’s skirt and asked when they were going. She stared at him a long moment, tea cup in hand, before sighing and calling for the carriage. She didn’t even bother to change into formal clothes this time, and the Wise Woman seemed surprised to see them at all. “Well, we might as well try while you’re here,” she said, her voice obviously doubtful.

William obediently held out the ring finger on his left hand and watched as the blood dripped into the bowl. “She has dark brown eyes,” William observed, “and some hair already.” He shrugged, and looked at the two women. “I suppose she’ll do. I’m just glad ‘tis over, and that I can go on with my life.”

“For you, perhaps,” his mother said, thinking of what she would now have to accomplish.

“Do not fret, mother, I shall write a letter to the little girl. Not that she can read it, anyway.” He petted his mother’s arm. He was a sweet boy, but he was always charging forward, never worrying about feelings.

The Wise Woman rolled out an elegantly painted silk map of the kingdom and all its regions, his mother smoothed the fabric across the table, and then the Wise Woman dipped a brass weight into the bowl. Henriette, William’s mother, placed her hands on William’s shoulders as the Wise Woman held the weight, suspended, over the map.

Henriette held her breath, waiting to see where it would land. Andrew, her younger son, had his intended living just down the street, which was quite convenient. At least they knew what they were getting into immediately.

The plumb-bob made huge circles around the map, spinning and spinning as the Wise Woman recited the words over and over. It stopped, stiffly pointing toward the North.

“Tarnia? Not possible, nor even probable. You must try again!”

For once, William’s mother wasn’t being stubbornly demanding. Tarnia, a place of cruel and wild magic, was the last place from whence one would wish a bride. They did not have Wise Women there, for anyone could perform spells. The Hags of the North ate their dead and sent the harsh winter wind to ravage the crops of the people of the South. Five hundred years ago, the North and the South had fought a bitter war over a cause no one could quite remember, only that it had been a brutal thing, and that many had died, and it led to the South losing most of its magic. Though the war was long over and the two supposedly united again, memory lingered.

“I have cast it twice.” The Wise Woman chewed her lower lip, but there was naught else she could do.

“Not Tarnia, please?” Henriette, usually a rather fierce and cold woman, begged.

“I am afraid so.” The Wise Woman began cleaning up; her shoulders set a little lower. “I am sorry.”

William, staring out the window at the children playing outside, couldn’t care less. What did it matter where anyone was from? She was a baby, and babies didn’t cause that much trouble.

“Only you, William,” his mother said, shaking her head. “Why can you not do anything normal?”

This was to be the tenor of most of their conversations throughout their lives.

Chapter 2

The Thirteenth day of Jarien, Sapphire Moon Quarter 1775

Miss Tasmin,

Since we are eventually to be married, and now that I have set forth on my own in order to secure our future, I suppose that it is my duty, as well, to get to know my intended a little more than I do now. So I have taken it into my head to write to you, and it is my hope that you will reply to my missives as best you may; the letters, and my receiving of yours, may be a bit sporadic since I will be at sea a great deal of the time, but it is better than nothing at all.

Now, if memory serves me, it is near the day of your birth, and since, again, if memory serves, you are soon to begin your seventh year, I have enclosed a doll. My sister-in-law-to-be favors this type a great deal, and so I believe that you might, as well.

Yours,

William

It was not, in fact, the first letter she had ever received from him, though it was far more eloquent than those that had come before. She kept the first missive with the others, but she never mentioned it for fear of embarrassing him, for it went, rather simply:

Hello. My name is William Almsley. I am seven years old today and I found out that we are getting married. I hope you are well, though being a baby I suppose you don’t really know. I like animals and the color blue. You shall have to tell me what you like when we see each other. Until then I hope you are happy.

William

While it was the one she read the least of all his letters, she still liked it, because as far as she could tell from its predecessors, he’d never really changed.

The fact was, Tasmin Bey did not mind her husband-to-be at all. She knew she was luckier than most, for few received anything at all from the one with whom they would spend their lives, as if they were all trying to forget the inevitable. William’s missives came four times a year, like clockwork. The ones that were meant to come around the Light Day celebrations and around her birthday brought with them a present wrapped in

good cloth, though the other two often held some trinket, such as an unusual plant or flower pressed in between thin slabs of preserving wax, a stone, a feather, whatever William thought she might find interesting. One had held a ring of coral that she wore still, on her smallest finger.

And she liked his letters. They were straight to the point, just like the very first, practical. He never wrote anything flowery or romanticized their match, but she thought he was kindly disposed towards her, and so she was happy enough.

She would have been quite content, if it wasn’t for the fact that everyone around her was quite determined to hate him.

“He’s from the Azin shore! Do you know what kind of people live at the Azin shore?” her uncle asked, accusing her as if she’d had a say in it.

“They used to eat their dead, according to Apercus’s Dictionary of the Peoples,” her father said. “Can you imagine such barbarity? And we’re sending our little girl into that that world? It’s disgraceful!”

“I suppose at the time there was a practical reason for them eating their dead,” Tasmin observed. “If William is any example of his people, practicality is quite his main motive of being.”

This, she found, was not a popular argument, and they finished their meal—an unfortunate choice of roast, considering the topic of conversation—in complete and disapproving silence. That was not the first word on the matter, nor would it be the last.

“You are determined,” her mother said, scrubbing bleaching oils (meant to counteract the effects of Tasmin spending hours in the sun) into her skin with a slightly less than careful vigor, “to give your father a heart attack. And me! What about me?”

“Mamma,” she said, “what exactly am I to do about this? He is my chosen, and I think it is good that we get to like each other before... ” she changed “before we start making children” to “…we begin living together.”

“I know.” Her mother sighed. “But they are such awful people. Nothing like us. During the war... ”

“Five hundred years ago,” Tasmin interjected.

“They took any prisoners they found with the gift and murdered them outright. It didn’t matter if they were Finders or Healers or Beast-Charmers or those with real power, they were all slain before you could pray for their souls. And you know what happened to them after that.”

“Aye, the Lord in His wisdom made it so that any born in the South lost most, if not all, of their Talents. You’d be hard pressed to find a Fire-Starter among the lot.” She took the cloth off her mother and started rinsing off the bleach. “I wonder if William has any talents? He never told me if he was tested. I think all of their Wise Women come from Tericia, from the East.”

Her mother sighed a great martyr’s sigh, and helped Tasmin rinse her skin. “If you put in for the Circle, you will be exempt from having to wed. Alcide herself says that you are gifted with herbs. Think of the life you could have at the university, teaching the craft until finally Alcide passes on and her seat is left open. She will certainly request that you fill it.”

The words were filled with their own sort of magic. The University Circle ruled the town, and all the Circles in Tarnia ruled together. Their town was small, and her type of talent would mean that she wouldn’t have a part in any major governmental decisions, but she would be part of the body that created hospices and researched new ways of using magic to improve lives, and then implemented the changes. The King of Berengeny, who ruled all the quarters of the continent, was said to listen very closely to the councils. It was his ancestor who, three hundred years ago, had approved the Mating Spell, which (though most had forgotten, whether by choice or because of propaganda) had been first discovered by a council in the North. In any case, it was a life of comfortable beds and exotic meals, velvet and silk, and more parchments and books than Tasmin would be able to read in three lifetimes, plus access to the best quality herbs, stones, and working materials.

“I will think about it,” she said to her mother as they washed her hair.

“That is what you always say.”

“But I will. I am nothing if not obedient.” Then their conversation ended because her mother had dumped the rinse water over her head.

When her mother was gone, after pinning Tasmin’s hair up to keep it out of the water, Tasmin leaned back against the edge of the bath and thought of William. She had calculated his course, using his last letter to find out heading and rough position, and thought that it was likely that he was in the Sea of Disea by now. She wished she could picture him, but it was impossible. If the persons lived in different locations, it was decreed that they should never see each other before the bride was sent for, to prevent expectations from forming. Her mother had seen him during the spell and was not very tactful about his looks: “A sturdy, round-faced boy. Doubtless a chubby man.” Tasmin did not mind; she was not, herself, much to gaze upon and it would be better if her husband was not desirable. Well, too desirable, at any rate.

She thought his life quite exciting. He was most fortunate, for he was able to travel the world, going from port to port, trading for goods to be shipped back to his family’s warehouses, where merchants looked over the shipments and bought what they liked best. They were a merchanting family, had been for years, transporting and trading all over the world. William had told her once that he had lists of what people wanted, and he went and found the best places to fulfill them. He told her that he was doing as much of the shipping work now as possible, so that when they were married, if it seemed right, he could spend more time on land. Her letter back had approved greatly of this plan, for she had not wished for herself a life of widow’s walks and worry.

Maybe he likes me, then, she thought, looking at her toes, which were propped on the edge of the small tub.

She hoped so.

Chapter 3

Julait Twenty-Third, Gold Moon Quarter 1786

Dear William,

Allow me to congratulate you on becoming the Captain of your own ship. Your father must have much faith in you to allow you such responsibility, and I am very pleased for you. From your description she sounds quite well armed. Is it habit for a merchant vessel to have so very many guns? I quite wonder where you intend to store your provisions and goods!

Today my mother is quite displeased with me, for I have brought home a gaggle of homeless Wind Sprites. I was wandering near an old castle that is being torn down and heard them, or, rather, felt them, weeping most piteously. How could I leave such frightened creatures alone? I unbound them from the spell that kept them there, and they latched on to me. I will see if I can find a new, safe home for them.

Finally, I must beg a favor. Soon, I will graduate from my training and gain the title of Herb Mistress. At the ceremony, we are presented with our athames, knives that we use in spell casting and naught else. Anyone who is my family, or considered to be family, is asked to give something of brass or gold (for the athame is made of those materials) to be melted down and used to create the knife. My people believe that we are essentially creatures of energy and on everything we touch we leave an imprint of that energy, so something that was worn often has a great deal of its owner’s energy in it. The benevolent energy of those who (I hope) care for me will protect me when I cast or create spells. In this vein, I beg that you will give me but one of your brass coat buttons.

Yours, eventually,

Tasmin

His parents sat stiffly upright across the table from him, their tea untouched, as they tried to absorb what their normally obedient and practical son had just said.

William waited, knowing that eventually someone would break the silence, and that it would be better if it weren’t he.

“Are you out of your mind?” His father, Justin, was quite red-cheeked, displeased beyond reason, but, so far at least, trying to keep his head.

“I have served the family concerns for seventeen years now,” W

illiam said kindly. “I think that it is time I turn my life to the future—my wife-to- be, my own little business.”

“Turn your life to the future?” The servants would not have to listen at the door if his father kept to that volume, for they would be able to quite easily listen while working by the kitchen fire. “This is your future, you damned ungrateful boy!”

“And chocolate?” his mother said, as if it were a filthy word. “Who in his right mind would give up a place as part of a successful family business in order to open an establishment that sells nothing but chocolate? I have never heard of such an ill conceived notion in all my years. I do hope this is your idea of a joke.”

“I’ve never liked anything half so well as I like chocolate. Besides, Andrew will be fine by himself. If he needs help it’s not like I’ll be on the other side of the world any longer.”

“I cannot believe my ears.” She grabbed her husband’s arm. “If this was Andrew I would understand, but this is William. He’s the sensible one. The one you could always depend on to make the right choice!”

“The boring one,” William added with a smile, even though he’d never found Andrew to be exactly the pinnacle of excitement.

“Son? This fool in front of me is not my son!” William hoped his father would start breathing soon, for he looked ready to explode.

“You do realize that, since you are being forced to marry a hag from Tarnia...”

“Herb Mistress. Hags are different; they focus on different rites or some such. Anyway, ‘tis not generally considered a very kind thing to say, so I hope that when I send for her you shan’t use it in her hearing.”

The Chocolatier's Wife

The Chocolatier's Wife